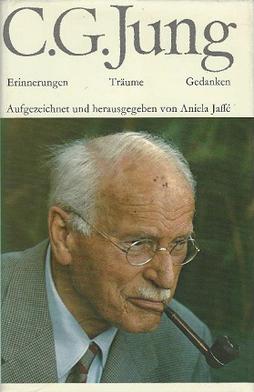

Memories, Dreams, Reflections is a partially autobiographical book by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and associate Aniela Jaffé. The book details Jung's childhood, his personal life, and exploration into the psyche. Wikipedia

..........................

“Memories, Dreams, and Reflections” by C.G. Jung

“The decisive question for a man is: is he related to something infinite or not? That is the telling question of his life. Only if we know that the thing which truly matters is the infinite can we avoid fixing our interest upon futilities, and upon all kinds of goals which are not of real importance. Thus we demand that the world grant us recognition for qualities we regard as personal possessions: our talent and our beauty. The more a man lays stress on false possessions, and the less sensitivity he has for what is essential, the less satisfying is his life. He feels limited because he has limited aims, and the result is envy and jealousy. If we understand and feel that here in this life we already have a link with the infinite, desires and attitudes change. In the final analysis, we count for something only because of the essential we embody, and if we do not embody that, life is wasted. In our relationships to other men, too, the crucial question is whether an element of boundlessness is expressed in the relationship.”

“Unless both doctor and patient become a problem to each other, no solution is found.”

“One gets nowhere unless one talks to people about the things they know. The naïve person does not appreciate what an insult is to talk to one’s fellows about anything that is unknown to them. They pardon such ruthless behavior only in a writer, journalist, or poet.”

“In many cases in psychiatry, the patient who comes to us has a story that is not told, and which as a rule no one knows of. To my mind, therapy only really begins after the investigation of that wholly personal story. It is the patient’s secret, the rock against which he is shattered. In therapy the problem is always the whole person, never the symptoms alone. We must ask questions which challenge the whole personality.”

“The psyche is distinctly more complicated and inaccessible than the body. It is, so to speak, the half of the world which comes into existence only when we become conscious of it. The psychotherapist, however, must understand not only the patient; it is equally important that he should understand himself. The patient’s treatment begins with the doctor, so to speak. Only if the doctor knows how to cope with himself and his own problems will he be able to teach the patient to do the same.”

“It frequently happens that women who do not really love their husbands are jealous and destroy their friendships. They want the husband to belong entirely to them because they themselves do not belong to him. The kernel of all jealousy is lack of love.”

“I feel very strongly that I am under the influence of things or questions which were left incomplete and unanswered by my parents and grandparents and more distant ancestors. If often seems as if there were an impersonal karma within a family, which is passed on from parents to children. It has always seemed to me that I had to answer questions which fate has posed to my forefathers and which had not yet been answered, or as if I had to complete, or perhaps continue, things which previous ages had left unfinished. It is difficult to determine whether these questions are more of personal or more of a general (collective) nature. It seems to me that the latter is the case. A collective problem, if not recognized as such, always appears as a personal problem, and in individual cases may give the impression that something is out of order in the realm of the personal psyche. The cause of the disturbance is not to be sought in the personal surroundings but rather in the collective situation. Psychotherapy is hitherto taken this matter far too little into account.

Like anyone who is capable of some introspection, I had early taken it for granted that the split in my personality was my own purely personal affair and responsibility. Faust, to be sure, had made the problem somewhat easier for me by confessing, “two souls, alas, are housed within my breast”; but he had thrown no light on the cause of this dichotomy. In the days when I first read Faust I could not remotely guess the extent to which Goethe’s strange heroic myth was a collective experience and that it prophetically anticipated the fate of the Germans.”

“Our souls as well as our bodies are composed of individual elements which were all already present in the ranks of our ancestors. The “newness” in the individual psyche is an endlessly varied recombination of age-old components. Body and soul therefore have an intensely historical character and find no proper place in what is new, in things that have just come into being. That is to say, our ancestral components are only partly at home in such things. We are very far from having finished completely with the Middle Ages, classical antiquity, and primitivity, as our modern psyches pretend. Nevertheless, we have plunged down a cataract of progress which sweeps us on into the future with ever wilder violence the farther the farther it takes us from our roots. Once the past has been breached, it is usually annihilated, and there is no stopping the forward motion. But it is precisely the loss of connection with the past, our uprootedness, which has given rise to the “discontents” if civilization and to such a flurry and haste that we live more in the future and its chimerical promises of a golden age than in the present , with which our whole evolutionary background has not yet caught up. We rush impetuously into novelty, driven by a mounting sense of insufficiency, dissatisfaction, and restlessness. We no longer live on what we have, but on promises, no longer in the light of the present day, but in the darkness of the future, which, we expect, will at last bring the proper sunrise. We refuse to recognize that everything better is purchased at the price of something worse; that, for example, the hope of greater freedom is canceled out by increased enslavement to the state. The less we understand of what our fathers and forefathers sought, the less we understand ourselves, and thus we help with all our might to rob the individual of his roots and his guiding instincts, so that he becomes a particle in the mass, ruled only by what Nietzsche called the spirit of the gravity.”

“I then realized on what the “dignity”, the tranquil composure of the individual Indian, was founded. It springs from his being a son of the sun; his life is cosmologically meaningful, for he helps the father and preserver of all life in his daily rise and descent. If we set against this our own self-justification, the meaning of our own lives as it is formulated by our reason, we cannot help but see our poverty. Out of sheer poverty we are obliged to smile at the Indians’ naivete and to plume ourselves on our cleverness; for otherwise we would discover how impoverished and down at the heels we are. Knowledge does not enrich us; it removes us more and more from the mythic world in which we were once at home by right of birth.”

“The Indian’s goal (as in the country India) is not moral perfection, but the condition of nirdvandva. He wishes to free himself from nature; in keeping with this aim, he seeks in meditation the condition of imagelesness and emptiness. I, on the other hand, wish to persist in the state of the lively contemplation of nature and of the psychic images. I want to be freed neither from human beings, nor from myself, nor from nature; for all these appear to me the greatest of miracles. Nature, the psyche, and life appear to like divinity unfolded – and what more could I wish for? To me the supreme meaning of being can consist only in the fact that IT IS, not that it IS NOT or IS NO LONGER.”

“A man who has not passed through the inferno of his passions has never overcome them. They the dwell in the house next door, and at any moment a flame may dart out and set fire to his own house. Whenever we give up, leave behind, and forget too much, there is always the danger that the things we have neglected will return with the added force.”

“In general, emotional ties are very important to human beings. But they still contain projections, and it is essential to withdraw these projections in order to attain to oneself and to objectivity. Emotional relationships are relationships of desire, tainted by coercion and constraints; something is expected of the other person and that makes him and ourselves unfree. Objective cognition lies hidden behind the attraction of the emotional relationship; it seems to be the central secret.”

“The relativity of good and evil by no means signifies that these categories are invalid, or do not exist. Moral evaluation is always founded upon the apparent certitudes of a moral code which pretends to know precisely what is good and what evil. But once we know how uncertain the foundation is, ethical decision becomes a subjective, creative act. We can convince ourselves of its validity only by a spontaneous and decisive impulse on the part of the unconscious. Ethics itself, the decision between good and evil is not affected by this impulse, only made more difficult for us. Nothing can spare us the torment of ethical decision.

As a rule, however, the individual is so unconscious that he altogether fails to see his own potentialities for decision. Instead he is constantly and anxiously looking around for external rules and regulations which can guide him in his perplexity. Aside from general human inadequacy, a good deal of the blame for this rests with education, which promulgates the old generalizations and says nothing about the secrets of private experience. Thus, every effort is made to teach idealistic beliefs or conduct which people know in their hearts they can never live up to, and such ideas are preached by officials who know that they themselves have never lived up to these high standards and never will. What is more, nobody ever questions the value of this kind of teaching.

Therefore the individual who wishes to have an answer to the problem of evil, as it is posed today, has need, first and foremost, of self knowledge, that is, the utmost possible knowledge of his own wholeness. He must know relentlessly how much good he can do, and what crimes he is capable of, and must beware of rearding the one as a real and the other as illusion. Both are elements within his nature, and both are bound to come to light in him, should he wish – as he ought to – to live without self deception or self delusion.”

“The individual on his lonely path needs a secret which for various reasons he may not or cannot reveal. Such a secret reinforces him in the isolation of his individual aims. A great many individuals cannot bear this isolation. As a rule they end by surrendering their individual goal to their craving for collective conformity – a procedure which all the opinions, beliefs, and ideals of their environment encourage. Moreover, no rational arguments prevail against the environment. Only a secret which the individual cannot betray – one which he fears to give away, or which he cannot formulate in words, and which therefore seems to belong to the category of crazy ideas – can prevent the otherwise inevitable retrogression.

The need for such a secret is in many cases so compelling that the individual finds himself involved in ideas and actions for which he is no longer responsible. He is being motivated neither by caprice nor arrogance but by a necessity which he himself cannot comprehend. This necessity comes down upon him with savage fatefulness, and perhaps for the first time in his life demonstrates to him the presence of something alien and more powerful than himself in his own most personal domain, where he thought himself the master.”

“The man, therefore, who driven by his daimon, steps beyond the limits of his intermediary stage, truly enters the “untrodden, untreadable regions” where there are no charted ways and no shelter spreads a protecting roof over his head. There are no percepts to guide him when he encounters an unforeseen situation — for example a conflict of duties. For the most part, these sallies into no man’s land last only as long as no such conflicts occur, and come swiftly to an end as soon as conflict is sniffled from afar.

But if a man faced with a conflict of duties undertakes to deal with them absolutely on his own responsibility, and before a judge who sits in judgment on him day and night, he may well find himself in an isolated position. There is now an authentic secret in his life which cannot be discussed — if only because he is involved in an endless inner trial in which he is his own counsel and ruthless examiner, and no secular or spiritual judge can restore his easy sleep. If he were not already sick to death of the decisions of such judges, he would never have found himself in a conflict. For such a conflict always presupposes a higher sense or responsibility. It is this very rare quality which keeps its possessor from accepting the decision of collectivity. In this case the court is transposed to the inner world where the verdict is pronounced behind the closed doors.

Once this happens, the psyche of the individual acquires heightened importance. It is not only the seat of his well-known and socially defined ego; it is also the instrument for measuring what is worth in and for itself. Nothing so promotes the growth of consciousness as this inner confrontation of the opposites.”

“Man can try to name love, showering upon it all the names at his command, and still he will involve himself in endless self-deceptions. If he possesses a grain of wisdom, he will lay down his arms and name the unknown by the more unknown, that is by the name of God. That is a confession of his subjection, his imperfection, and his dependence; but at the same time a testimony to his freedom to choose between truth and error.”

“I am astonished, disappointed, pleased with myself. I am distressed, depressed, rapturous. I am all these things at once, and cannot add up the sum. I am incapable of determining ultimate worth or worthlessness; I have no judgment about myself and my life. There is nothing I am quite sure about. I have no definite convictions – not about anything, really. I know only that I was born and exist, and it seems to me that I have been carried along. I exist on the foundation of something I do not know. In spite of all uncertainties, I feel a solidity underlying all existence and a continuity in my mode of being.

The world into which we are born is brutal and cruel, and at the same time of divine beauty. Which element we think outweighs the other, whether meaninglessness or meaning, is a matter of temperament. If meaninglessness were absolutely preponderant, the meaningfulness of life would vanish to an increasing degree with each step of our development. But that is – or seems to me – not the case. Probably, as in all metaphysical questions, both are true: Life is – or has – meaning and meaninglessness. I cherish the anxious hope that meaning will preponderate and win the battle.

When Lao-Tzu says:

“All are clear, I alone am clouded,” he is expressing what I now feel in advanced old age. The more uncertain I have felt about myself, the more there has grown up in me a feeling of kinship with all things. In fact it seems to me as if that alienation which so long separated me from the world has become transferred into my own inner world, and has revealed to me an unexpected familiarity with myself.”

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memories,_Dreams,_Reflections